Andragogy is a pedagogy adapted to adults. (1)

It primarily deals with education. This article is the follow-up of our previous article on the subject, published two weeks ago. (2)

In this second part, we will cover the last three items of the andragogy system developed by Knowles. (3)

Japan is a hierarchical cultural society, and andragogy is not the best system for their culture. Westerners can benefit from andragogy because we have Descartes’ logical approach to life. We need to understand to accept. The Japanese don’t; they must comply. Japan has been an obedient society since the Kamakura Jidai by Minamoto Yoritomo. (4) (5)

Hatsumi sensei said that “Japanese don’t understand Budō.” It might be because of that. Obeying mindlessly to a system without understanding leads to a loss of creativity. And Budō is all about creativity.

In the first part, we covered the first three items of andragogy: Need to know, Strong foundation and Self-concept. Knowles says adults are interested in “Readiness” or, to put it straight, “How can this benefit me?” Knowles defines Readiness as “adults are most interested in learning subjects directly relevant to their work and personal lives”. As Budō teachers, we do the same. I always ask three questions to any new student coming to the dōjō: “Age or family, past budō experience(s), job.” With a few pieces of information on his age and family situation (spouse, siblings, kids), It gives you some understanding on his mental development. Past Budō experience explains their reactions on the mats, how they walk (i.e. their relation to space) and their vision of the world. Knowing their professional world gives you a glimpse of their mental process and access to their daily dictionary. We use a specific dialect in the workplace when interacting with our peers. But each time we join a new group, we must learn another vocabulary. I discovered that using IT analogies with an IT guy, physiology with a nurse, or car parts with a mechanic shortens the time to acquire new knowledge. (6)

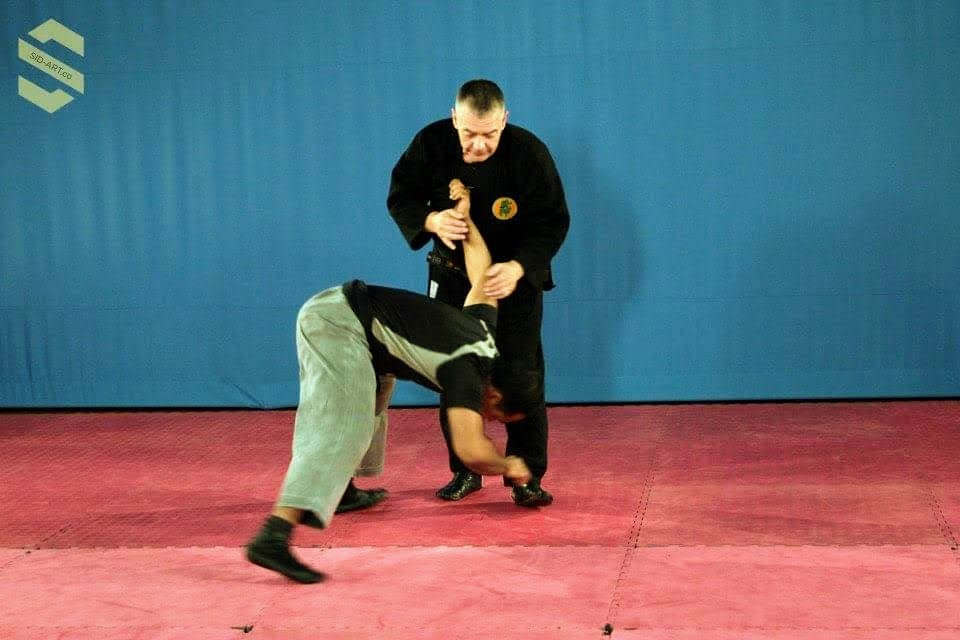

The fifth item is what Knowles calls “Orientation”. I prefer “reason”. What it means is that adult learning is problem-centred rather than content-oriented. Put differently, teachers should do their homework to know why things are done in a specific order or manner. That is why basics are an essential part of our training. I remember teaching once at a prestigious school of Engineering. I explained the power of Boshi ken compared to Fudō ken when my Uke turned to his peers and said, “Yes, power = force/surface.” This happened in the 90s. Since then, I have used it every time I have engineers in front of me. Adults need solutions to their problems. They feel they are losing time when you only teach theoretically.

Last is “Motivation.” This one item is partially linked to the previous one. Adults respond better to internal versus external motivators. They must be motivated and feel the gain that regular training brings. If when they begin, they often dream of becoming a modern ninja (sic.), they want their studying time to benefit them (physically or mentally). I travelled a lot to Japan, and each time, I came back more affluent than before. Now, motivation can be destroyed by personal difficulties (job, studies, family); in that case, don’t overthink and apply the “never give up” attitude. These highs and lows are logical. Keep always the big picture in mind.

In Japan, pedagogy is Kyōjuhō, which is composed of “teach+instruct+rule.” (7) It is not limited to the education of youngsters, but the word “Androgogy” doesn’t exist, no surprise here (cf. what I wrote at the beginning). The word Jōnindenshō made up of Jōnin (adult) and denshō (transmission), seems to be the best to explain how we need to transmit Budō to adults. (8)(9)

As a teacher, if you use these six steps when teaching adult classes, I can guarantee an acceleration in learning.

Teach the NeSSROM to your adults:

- Need to know,

- Strong foundation,

- Self-concept,

- Readiness

- Orientation,

- Motivation

And you will help them reach their potential. They are adults. They have already constructed their life. They are not going to war any time soon. Be authentic and teach them what they need to become better humans. They need Budō to continue their evolution.

If you educate the Jōnin (adults) with andragogy, they turn into Chōnin; they go from adults to “supermen” or “Übermensch”, as Nietzsche defined it. (10)(11)

Andragogy is the best tool to achieve that.

_____________________________________

1 Andragogy refers to methods and principles used in adult education. The word comes from the Greek ἀνδρ- (andr-), meaning “man”, and ἀγωγός (agogos), meaning “leader of”. Therefore, andragogy means “leading men”, whereas “pedagogy” literally means “leading children.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andragogy#:~:text=Andragogy%20refers%20to%20methods%20and,%2C%20meaning%20%22leader%20of%22.

2. https://kumablog.org/2023/10/01/do-you-believe-in-andragogy-or-pedagogy-part-1/

3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Knowles

4. Minamoto put the Samurai class above all others. He reorganised the empire, and disobeying was punished by death. That was in 1185. Eight centuries later, today’s structured society makes it nearly impossible to apply andragogy.

5. More on Kamakura Jidai (鎌倉時代, Kamakura jidai, 1185–1333): https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamakura_period

Sidenote: “jidai” 時代 means period, epoch, era, age. Please do not mistake it for the Starwars Jidai.

6. Takamatsu sensei said we must be curious about everything when studying Budō. That could be one of the reasons.

7. 教授法 kyōjuhō: Pedagogy = teach +instruct + rule(s)

8. 成人, jōnin or seijin: adult

9. 伝承handing down (information); legend; tradition; folklore; transmission

10. 超人, chōnin: superman or Übermensch as defined by Nietzche in Zarathustra.

11. Übermensch: For Nietzsche, the Übermensch is a being who can completely affirm life: someone who says ‘yes’ to everything that comes their way; a being who can be their determiner of value; sculpt their characteristics and circumstances into a beautiful, empowered, ecstatic whole; and fulfil their ultimate potential to become who they truly are.